Benjamin Schultz, Ph.D. Geography

There are very few events that have the ability to bring people together (or to push them apart) quite like sports. Sports franchises possess the ability to become the public face of an entire city. As such, big-city mayors from Boston to San Francisco are jumping on board to participate in the current boom in the construction of sports-related facilities. According to the Brookings Institution, American cities spent over $7 billion on new facilities in the first decade of the 2000s, most of which came from public sources.

Of all the reasons cities choose to subsidize the construction of sports facilities, there is one reason that gets far more press than any other: job creation. New jobs mean overall improvement in the local economy, and proponents of building new sports facilities expect that to happen in four ways. First, just building the facility creates jobs in the construction industry. Second, the events hosted in these facilities attract tourists and locals alike, which creates jobs in the accommodations and hospitality sector and causes new spending. Third, the teams themselves have employees, who in turn spend their money locally. Fourth, new spending creates a multiplier effect, which in turn creates more spending and economic growth in the form of increased sales tax and property tax.

There are various measures available to test whether or not new sports facilities actually have much impact on improving the local economy. One is to observe if there is an increase in the gross regional product, which is a measure of the value of all goods and services in a particular city. Economists also measure the increase in local salaries and wages, job growth in relevant sectors and the decrease in unemployment.

In the U.S., the rise of Major League Soccer (MLS) offers a great opportunity to examine the economic impact of new sports facilities. While its popularity has yet to reach the level of the other major professional sports leagues, the MLS is actively expanding and attracting major financing for new soccer-specific stadiums to be built. Prior to 1999, all teams in the fledgling league shared field space with other local sports teams. Since 1999, the league has constructed 13 new soccer-specific stadiums, with more planned in the near future.

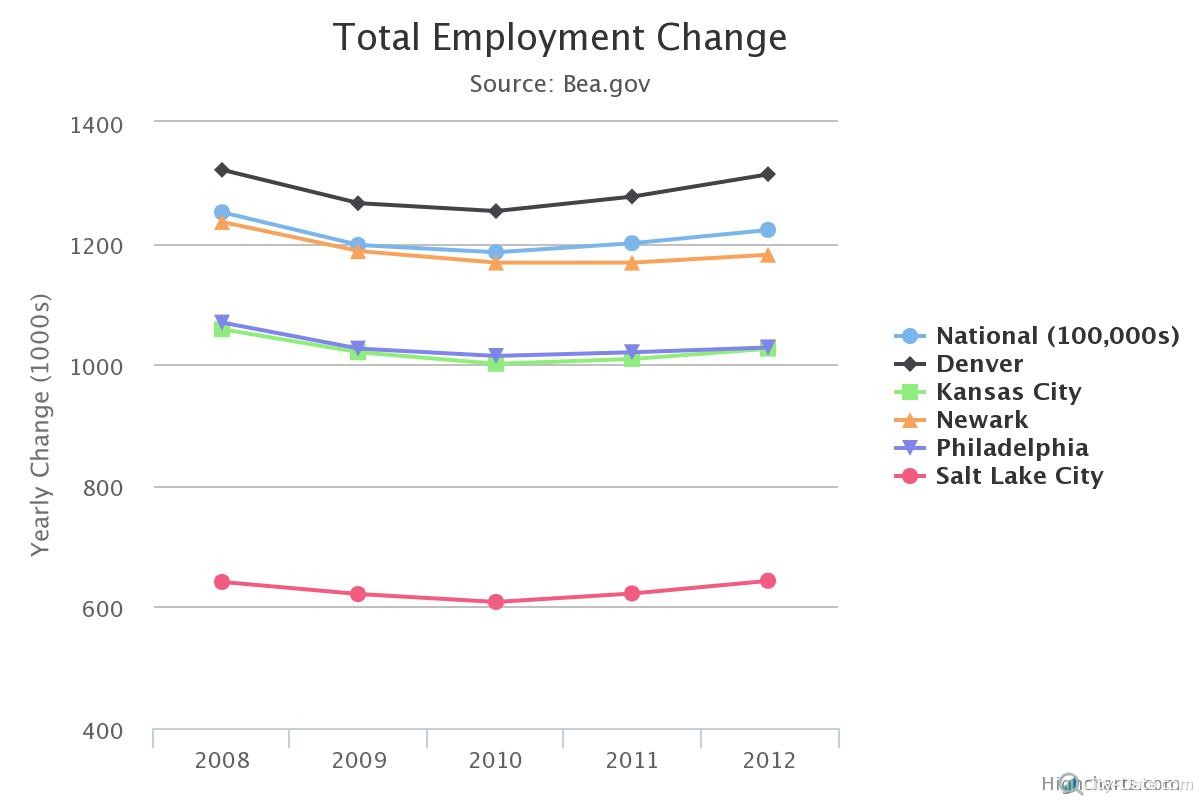

To get a sense of how soccer-specific stadiums impact the local economy, this post examines the changes in wages and employment in the construction, retail and food and hospitality industries in five U.S. cities that completed a new MLS stadium between 2007 and 2011. Those cities and their respective teams are Philadelphia (Union), New York (Red Bulls), Kansas City (Sporting KC), Salt Lake City (Real Salt Lake) and Denver (Colorado Rapids). For the sake of clarity, the Philadelphia Union’s PPL Park is located in Chester, Pennsylvania, and New York’s Red Bull Area is actually in Harrison, New Jersey. To make the analysis more precise, data for Philadelphia actually correspond to the metropolitan division of Montgomery-Bucks-Chester County, while data for New York correspond to the metropolitan division of Newark.

The charts below represent the total wages earned in a given industry. Wages in the construction industry, one of the hardest-hit by the economic downturn, are lower than they were at the start of the recession, although they have experienced steady year-to-year growth in all cities. None of the cities have returned to their pre-recession levels, and Denver’s wages remain lower than they were in 2009, the year after the bottom fell out of the economy.

According to proponents, new stadiums should have a multiplier effect on the local economy, especially in the accommodations and food industry and retail industry. Wages in accommodations and food have experienced strong growth since the recession. Only Kansas City falls well below the national average growth for the whole period, but it still displays a positive trend.

Growth in retail wages has been slower at the national level, and they have even declined in Philadelphia. The growth of retail wages in Salt Lake City, on the other hand, has been very strong at over 12 percent, and growth in Kansas City and Denver is also well above the national average.

The other measure that can be used to examine the economic impact of a stadium is job growth. With respect to overall job growth, only Salt Lake City has actually increased the total number of jobs since the 2008 total. At the industry level, total employment in the construction sector shrank by nearly 20 percent between 2008 and 2012, both nationally and in the respective cities. Likewise, according to 2012 data, the retail sector had yet to fully recover from its 2008 level in any of the five cities. Only the accommodations and food sector has fully recovered from its recession-level lows, although only in Newark does the rate of recovery surpass that of the national average for all metropolitan areas.

Clearly, there are more factors influencing these numbers than one stadium. At the same time, they do not necessarily signal a ringing endorsement for the idea that new stadium construction is a significant boon for the local economy. If anything, these findings lend support to the contention that any increased shopping and dining out activity in the vicinity of a new sports facility is simply a replacement for similar activities that would have happened elsewhere in the city. Rather than having a drink and then going to a movie in one part of town, a person may have a drink near the stadium and then go a game. Either way, the amount of money being spent is not significantly different. What is different is the fact that all citizens, regardless of their interest in actually attending any events at the facility, are on the hook for its construction and maintenance. While fans of these teams many enjoy boasting about the quality of their stadium, data show that the costs are likely to outweigh the benefits when it comes to the construction of new sports facilities.

About Benjamin Schultz

Benjamin Schultz, Ph.D. Geography

Benjamin is currently an Assistant Professor of American Studies at International Balkan University in Skopje, Macedonia. He received a Ph.D. in Geography from the University of Tennessee, where he also taught courses on Urban Geography, Appalachia and World Geography. His main academic interests are urban and economic geography in Europe and North America.

Other posts by Benjamin Schultz: