Benjamin Schultz, Ph.D. Geography

In terms of its significance to symbolism and cultural imagery, perhaps nothing is more quintessentially “American” than the Intermountain West (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming). The West is a living metaphor for values that so many Americans identify with, such as freedom, independence, individualism and self-reliance. The region is also home to some of our most iconic national parks like Yellowstone, Glacier and Grand Canyon.

Quietly and gradually, however, the Intermountain West has come to represent another essential part of the American story: change. Over the past 30 years, parts of the Intermountain West have experienced significant demographic, economic and political transformations. A “New West,” associated with high-tech startups, adventure seekers, and quality-of-life migrants, now stands alongside the “Old West,” which is associated more with mining, ranching and timber.

How exactly those differences bear out in empirical terms is something that merits further consideration. What places can we say represent the New West, and what are their characteristics? How do these characteristics compare to those of the traditional Old West, and what can we learn from those disparities?

A straightforward way to answer these questions is to use a statistical clustering technique called a k-means to identify the similarities and differences among the counties in all of the states in this region. This strategy yields four distinct categories that allow us to identify exactly what the differences are between the New West and the Old West. Of the 280 counties in this region, 44 have characteristics that are more closely aligned with the New West, while an additional 82 counties are in a state of transition.

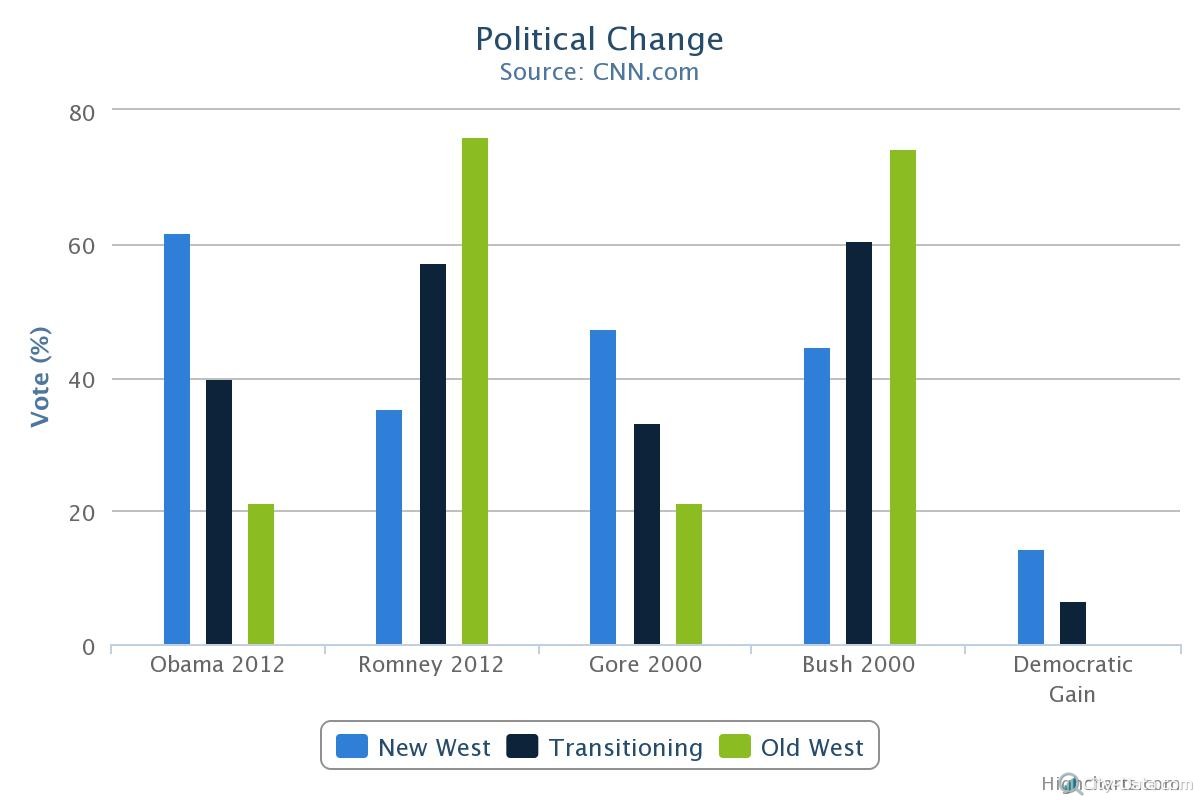

With respect to politics, almost 62 percent of New West counties voted for Obama in the 2012 presidential election. In comparison, Obama won only 21 percent of Old West counties. The most significant feature of this statistic, however, is the growth of Democratic support since the 2000 election, when Gore won only 47 percent of the same counties that now identify with the New West. As the chart below demonstrates, Republican support in the Old West has remained strong throughout. Obama only won 40 percent of the transitioning counties, but that figure is 7 percent higher than Gore received in the 2000 election.

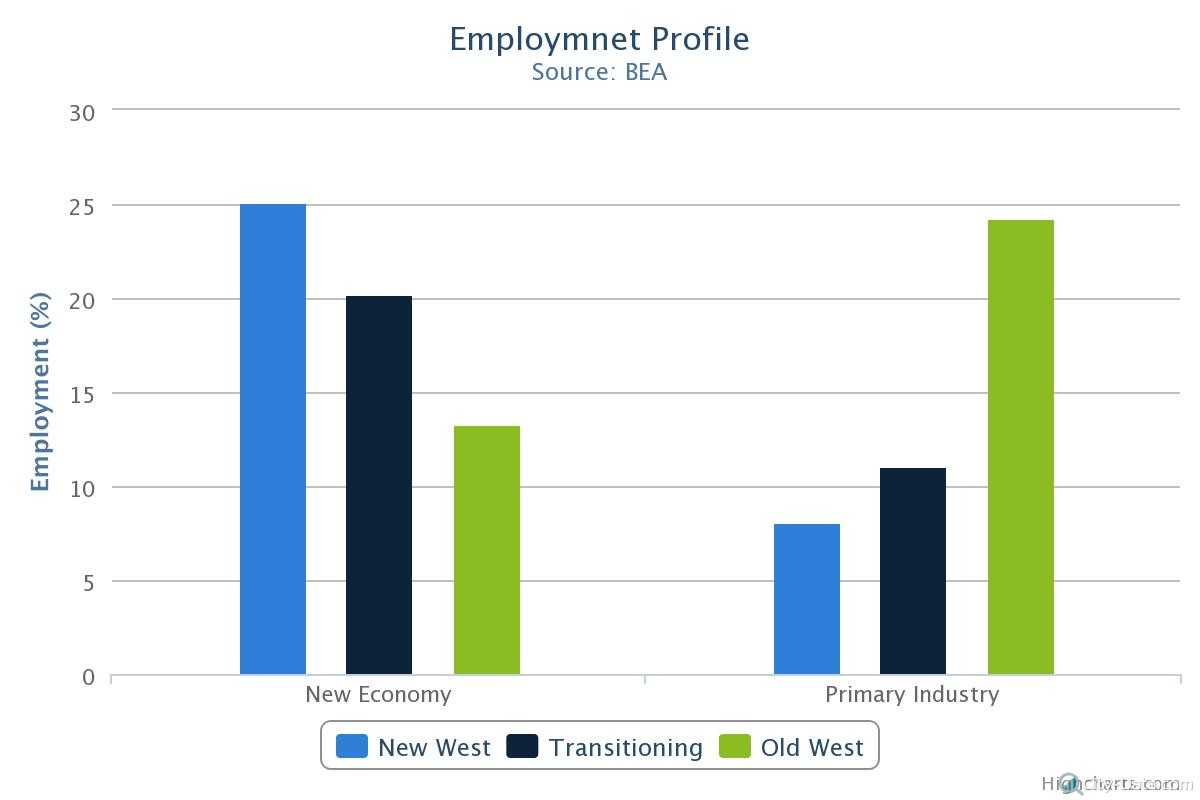

The difference between the two categories is also evident in economic terms. One-quarter of employment in New West counties is associated with creative class technical professions or with arts and recreation, which includes tourism and related services. Only 8 percent is related to the primary sector. The situation is nearly the opposite in the Old West, where one-quarter of employment is in the primary sector and only 13 percent of employment is related to the “new economy” or to arts and recreation services. The new economy comprises 20 percent of employment in transitioning counties, while 11 percent is tied to the primary sector.

Demographic characteristics are in many ways related to the economic characteristics of the two types of places. Over 11 percent of adults over the age of 25 have a bachelor’s degree or higher in New West counties, compared to less than 6 percent in the Old West. Likewise, per capita income is $3,000 higher in New West counties. To a large extent, these differences are a reflection of the types of jobs many people in the respective types of counties have. Jobs that have technical aspects or a research component tend to require advanced education, which is also strongly correlated with higher incomes.

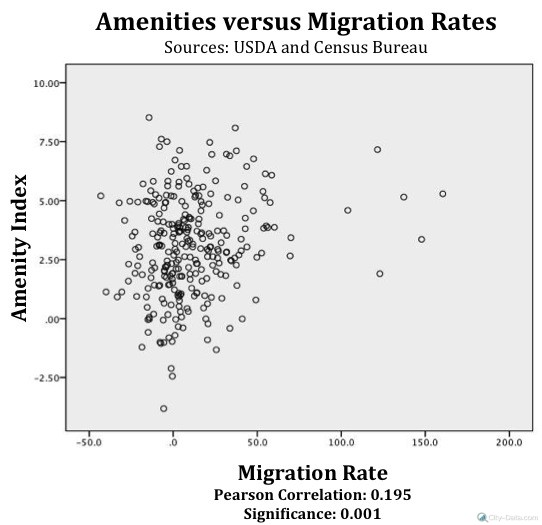

Perhaps the most telling distinction between the New West and the Old West, however, is the correlation between the net migration rates of young adults (ages 25 to 39) and natural amenities. “Natural amenities” refers to physical features like rivers, lakes and mountains that can be enjoyed for their aesthetic beauty or for their recreational uses. Researchers at the USDA devised an index to measure the physical characteristics of a county compared to others.

In the past few decades, many communities with abundant natural amenities have been able to capitalize as young professionals from the city move to have access to hiking in the rugged mountains, whitewater rafting or rock climbing. This is especially true of young professionals who no longer move to a new location simply because of a job; the physical characteristics of a location and access to natural amenities are becoming increasingly important.

Teton County, Wyoming, known for Jackson Hole and Yellowstone National Park, stands out as a prototypical example of a New West county. Teton County has a net migration rate of 53.4 for young adults between the ages of 25 and 39, and nearly 40 percent of its employment is tied to the service economy. After Bush won 53 percent of the vote in 2000, Obama won 55 percent in 2012, reflecting the general political trend in many New West counties.

Although the scale is much smaller, San Juan County, Colorado, has a similar demographic and political profile and is second only to Los Alamos, New Mexico in its percentage of new economy employment. Young adults have migrated to San Juan at a rate of 121.5, which is one of the highest rates in the region. In the last presidential election, the Democrats picked up 18 percent more of the vote compared to 2000, helping Obama win the county by an 11-point margin.

In sum, New West counties such as Teton and San Juan share some basic characteristics. First, they are marked by a shift from the primary sector (extraction of natural resources) to the tertiary sector (diversified services). The drive towards a service economy in the New West has also brought demographic and political consequences. Demographically, the New West is younger, wealthier and more educated than the Old West. In keeping with the political tendencies of this demographic, the New West is also more liberal than its staunchly Republican counterpart. Because of its growth and the continuing trend among young adults to move closer to natural amenities, this shift has potentially far-reaching political consequences that could play out at both the national and regional scales.

About Benjamin Schultz

Benjamin Schultz, Ph.D. Geography

Benjamin is currently an Assistant Professor of American Studies at International Balkan University in Skopje, Macedonia. He received a Ph.D. in Geography from the University of Tennessee, where he also taught courses on Urban Geography, Appalachia and World Geography. His main academic interests are urban and economic geography in Europe and North America.

Other posts by Benjamin Schultz:

These points will be interesting as we await the outcome of the the coming election and the Iowa caucus. What I find to be the current problem in, say, a high-density area like Albuquerque, NM as opposed to Teton is the lack of resources allocated to support growing populations ie., education, employment, etc. which is in part due to state as well as Fed government aid allocation. That said, in a lot of ways I feel the Old West that you point out here is merely a nostalgic concept. These Old West industries ie. mining, timber, etc and their ability to sustain a local economy went the way of the dodo years ago.